2015 marks the 10-year anniversary of when I “quit my day job,” and launched Sarah Sloboda Photography full-time.

10 years! How crazy is that? In 2005, a young woman walked out of what was already a great job in search of her dream, and 10 years later, the endeavor is going strong.

It would have been hard for me to imagine what I have accomplished. There was a lot of putting one foot in front of the other. Long walks and daydreaming at times, yes, but most working hours spent buckling down and trying to get from one week to the next.

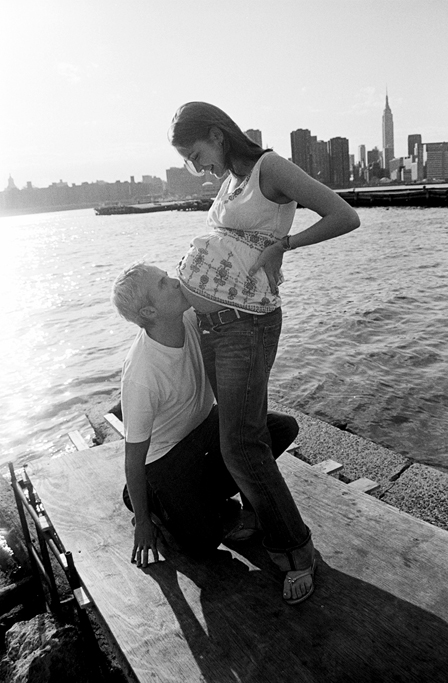

As an artist, I wanted to make the camera create something that felt like memories to me — that captured enough ambience and etherealness to feel like a real moment in the emotional sense but without being haphazard, so that a viewer’s eye would rest upon it pleasantly.

Often out of hundreds of images, only one stood out as having real resonance with anything. Most images were failures, and even the successes now don’t look as successful in retrospect. I kept learning and studying the work of people I admired: photographers, jazz musicians, actors, painters, architects, writers. This thing that we chase as an artist, how do we capture it?

A lot of art appreciation education talks about definition – what is this thing the artist is trying to capture? But I’ve never felt much preoccupation with definitions. I like ambiguity, and I like imagery to speak for itself, on many levels, without the limitations of language.

Once after a long set, my friend jazz guitarist Randy Napoleon commented that he’d never seen anyone so rapt for so long, listening to straight-ahead jazz. I had sat in the audience and listened, doing nothing else for several hours. I paid careful attention to the melodies and what liberties were taken, and how the musicians responded to one another’s liberties.

Randy gave me a great piece of advice. He said, “Never study music. You love it too much. Live in the love, and don’t intellectualize it.”

In film school, I had learned to turn a recreational activity like movie-watching into a cerebral endeavor, and a lot of that bled into my photography work. Randy’s comment made me realize that for me, authentic art is a balance between the mind and the heart. I needed to embrace my wonted disregard for definitions and let what I had studied blend into my subconscious, where vivid childhood memories morph with dreams of alternate worlds, and of our own future in this one.

I realized people don’t really like being defined, either. They want to be recognized for all their myriad qualities, those harmonious as well as those that seem incongruent. When I photograph people, it’s about who they are in that moment. Who they’re willing to be for the camera and me. They can be somebody else tomorrow or in 10 years, and that’s the whole point of photographing now. So we can look back and see how far we’ve come, which weaknesses became our greatest strengths, which inner enemies our allies.

Over time (there’s that whole 10,000 hours thing), what was once only potential started to show itself in the work, and became something I felt proud of. All those baby steps turned into images that I hope deeply serve my clients’ desire to capture moments of fast-paced lives.

But if you asked me how exactly this happened, I’m not sure. I kept showing up to do the work, adding more heart when the mind took over, adding more mind when something wasn’t clearly articulated. I looked at what I had shot, loved what worked about it, and knew what didn’t, and tried again and again, until I got better.

Two things I think I did right: One, I appreciated what I was doing. Even photos that I now look back on and roll my eyes, at the time, I allowed myself to love them because they had come from me. Embarrassing perhaps, but it was a lot like a child coming home from school with a drawing and wanting it hung on the fridge. Appreciating my work kept me going.

And the second thing was that I quit my day job first. I didn’t wait for a good time or fool-proof opportunity. I made it so that if I didn’t work, I wouldn’t eat — ok, that sounds dramatic. But I wanted it to be what I did for a living so that I had no excuses. To stay in business, I had to figure out how to do good work, and offer people something that was worth more than what they paid for it. There was no back-up plan. “Make good photos” was the only plan. A bit naive, probably, but going all in served me.

There is still a lot I want to do, and I still want my photos to keep getting better, but I think it’s important to take stock and appreciate what has been accomplished. It’s strange, but I remember sitting at my desk about to give notice at what would be my last salaried job. It was such a huge leap, and what if I couldn’t hack it? To ease my fears, I thought to myself, “Don’t worry. You don’t have to do this forever.” It’s amazing how one moment’s decision can turn into 10 years of growth, success, and self-fulfillment, when you take the pressure off.

The images in this post are from my first printed portfolio, taken 2005-2007.